Being shot in the stomach isn’t one of the most effective ways to prolong life, which is why Alexis St. Martin’s story is so surprising. Not only was he shot from a few meters away on June 6, 1822, when he was almost 20 years old, but he was able to live another 50 years even though the wound never fully healed, providing doctors at the time with a window, literally, on the way the human body digests food.

Alexis St. Martin was an illiterate French-Canadian who worked as a trapper for the American Fur Company, and the man who shot him in the stomach also worked as a trapper at the Mackinac Island factory in the United States. It’s not entirely clear what happened, but most accounts claim the incident occurred when St. Martin’s partner accidentally discharged his weapon.

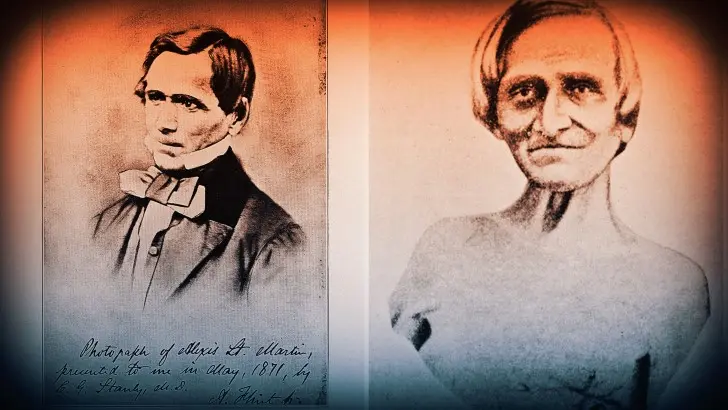

The story of William Beaumont and Alexis St. Martin.

Half an hour later, St. Martin was examined by Mackinac Island’s resident military physician, Dr. William Beaumont, and what he observed was anything but pleasant:

The [shot] entered from the rear and in an oblique direction, up and in, literally flying integuments and muscles the size of a human hand, fracturing and displacing the anterior half of the sixth rib, fracturing the fifth, lacerating a portion of the lower lobe in the left lung, the diaphragm, and piercing the stomach.

All this mass of materials pushed by the musket, along with fragments of clothing and fractured ribs, ended up lodging in the muscle and chest cavity…

And it continues.

A piece of lung, the size of a turkey egg, was found protruding from the external wound, lacerated and burned, and immediately below another protrusion which, on further analysis, revealed to be a portion of stomach, lacerated in all layers and expelling food which the patient had eaten for breakfast, with a hole wide enough to insert the index finger.

After reading Dr. Beaumont’s description, it is understandable that his prognoses were anything but encouraging and he expected St. Martin’s death no later than that night. However, he operated on him as best he could, and against all expectations, Alexis St. Martin ended up surviving.

A hole in the stomach.

The problem arose when St. Martin made his first attempts at drinking and eating. Because of the hole in his stomach, any swallowed substance ended up being expelled shortly after through the hole. Not in the mood to give up, Beaumont spent several weeks feeding St. Martin “nourishing enemas,” a technique that allowed the patient to recover.

After a few weeks of treatment, Beaumont decided that feeding through the rectum was no longer necessary, although the hole in the stomach was still present. The solution to this problem was to place “bandages and duct tape over St. Martin’s wound to block the food from leaving.”

In the notes, Beaumont clarifies: “no unusual illness or irritation in the stomach, not even the slightest hint of nausea manifested itself during all this time; and after the fourth week the appetite became good, the digestion regular and the natural bowel movements, and all the functions of the system are perfect and normal.”

By the fifth week, St. Martin had healed excellently except for the troublesome hole in his stomach. Instead of healing naturally, the hole had more or less stuck to the skin, giving rise to a kind of sphincter with a slight prolapse of the stomach pushing on it. This necessitated the continuous application of bandages to ensure that St. Martin retained solids and liquids.

Dr. Beaumont’s experiments on digestion.

Eight months later, Dr. Beaumont was exploring a variety of methods, sometimes very painful, to get the hole to close on its own but failed irretrievably. At one point he suggested cutting the connection between the stomach and the skin and stitching everything back together, but by then St. Martin had had enough. Since he was a fully functional and healthy man, not to mention that he literally had a hole in his stomach, he decided not to have the surgery.

While all this was going on, St. Martin’s contract was cancelled and he was expelled from the hospital because he had no money to pay for it. However, Dr. Beaumont saw in this man a unique opportunity to personally study the human digestive tract… And when we say personal, we don’t mean it in the figurative sense of the word.

For example, during one of his many examinations he literally stuck his tongue into the orifice and noted: “when the tongue is applied to the mucosal layer of the stomach, empty and without irritation, no acidic taste can be perceived.”

At the time, medicine was virtually unaware of the exact mechanism of the digestive tract in humans. Most experiments were done on animals, and inevitably ended with the death of the animals, so observing a functional digestive tract was not feasible. Dissecting human corpses was also not very useful for appreciating the process of digestion in the living organism.

In an attempt to circumvent these obstacles, doctors tried things like tying cords to mesh bags that they then swallowed, waited a certain amount of time, and then pulled them out by the mouth. However, no one had ever had the opportunity to experiment with someone like St. Martin.

The escape of Alexis St. Martin.

For this reason Beaumont offered to hire St. Martin as a servant, mainly to perform laborer jobs, but under an explicit agreement that the doctor could perform experiments on St. Martin at will. Given the contract agreements and St. Martin’s very precarious economic and social situation, there was little respect for the things this man wanted once he signed.

Although the terms of that first contract are unknown, a second contract between St. Martin and Dr. Beaumont managed to survive the test of time and specifies that for becoming Beaumont’s servant and guinea pig, St. Martin would receive a payment of $150 per year.

After a few years in this situation, St. Martin sent the contract down a tube and went to Canada, where he managed to settle down and start a family. Disturbed by the situation, but still intent on studying St. Martin, Beaumont shelled out large amounts of money tracking him down and subsequently tried to convince the fur company St. Martin worked with to allow him to return.

He offered her various incentives such as increased payments, land granted by the government, and financing to move her family (or money to abandon her wife and children). Privately, however, he reportedly wrote, “When he returns to my care, I will control him as I please.”

In another letter he also referred to St. Martin’s sons as “living replacements,” and in a letter sent to the U.S. surgeon general lamented St. Martin’s “stubborn and villainous ugliness.” Moreover, when he referred to St. Martin, he did so by the term “boy” rather than by his name.

A window into the digestive tract.

But before all this, with all those humiliations that forced St. Martin to run away from the doctor’s “care,” Beaumont basically spent his time poking around in St. Martin’s stomach to see what was going on, and we say “see” because he often used all kinds of instruments to stretch the hole so he could watch the food and drink being digested. noting that in this way “you could observe up to 5 or 6 inches deep.”

In addition to poking at the wound with his tongue, he would occasionally remove things from inside such as stomach tissue and food. On the latter, after extraction he even dared to test the material; For example, he went so far as to write that partially digested chicken had a “mild and sweet” taste.

Beaumont also became obsessed with stomach acid, which he experimented with separately, and went so far as to send samples to other doctors who were also conducting experiments. Of the awkward procedure, he noted:

When the probe is inserted, the fluid quickly begins to drain, first in droplets and then in a continuous flow, occasionally in a short continuous flow. Moving the catheter up, down, backward, or forward increases drainage. Typically, the amount of fluid you get is equivalent to one or two ounces.

After the extraction, there is a particular sensation in the pit of the stomach, which he referred to as sinking, with a certain level of fainting that makes it necessary to stop the procedure. The ideal time to extract gastric juice is in the morning, before eating, when the stomach is clean and empty.

The body adapts.

And although the wound never healed, Beaumont described a very rare phenomenon that occurred about a year and a half after the gunshot:

Now, a small fold of the stomach layers formed over the upper margin of the orifice, protruding slightly and increasing in size until it filled the opening, replacing the need to apply bandages to retain stomach contents. The valve ended up adapting to the accidental orifice in a way that prevented the total exit of the gastric contents when the stomach was full.

Thus, while the hole in St. Martin’s stomach and abdomen was still present, the stomach tissue formed a sphincter, so that St. Martin no longer needed to apply bandages to avoid spilling the contents of his stomach.

The end of Alexis St. Martin.

Be that as it may, the many discoveries Beaumont made in the years he experimented with St. Martin eventually earned him the title of “father of gastric physiology,” helping to lay the groundwork for modern understanding of the digestive process in humans.

Incredibly, St. Martin lived to be 78 years old and had 6 children with a practically normal life.

At the time of his death, doctors requested information to acquire St. Martin’s body, but family members had already foreseen the scenario. According to some reports, they left the body in the sun for several days until it began to decompose and then buried it in a secret grave, all to prevent anyone from digging it up for an autopsy.

Regarding the specific requests made by these doctors, a rather audacious doctor sent a medical bag to St. Martin’s family to have the stomach returned. Instead, family members returned a note that said, “Don’t come for the autopsy, they’ll kill you.”